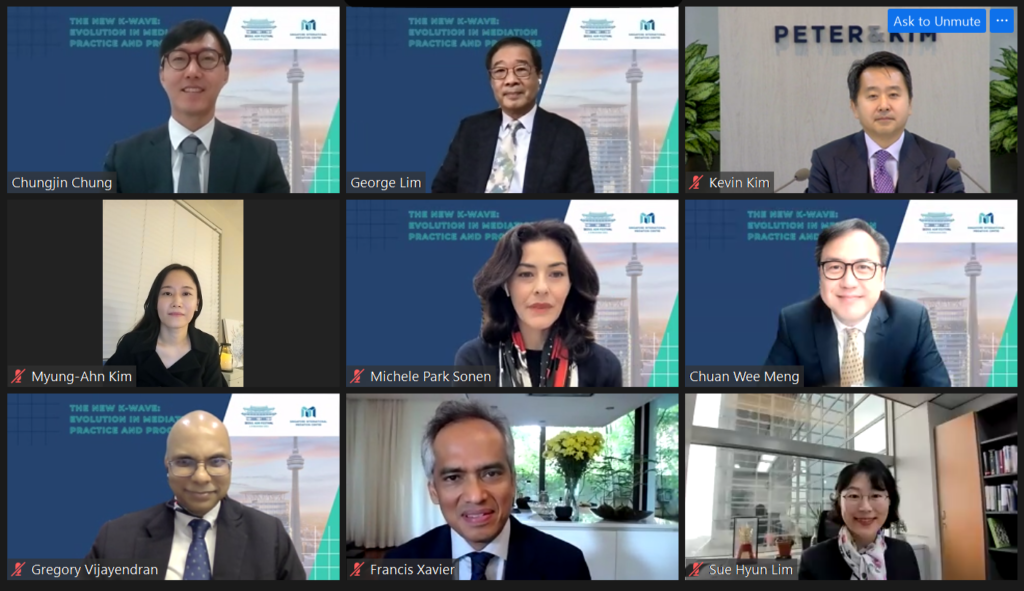

On 1 November 2021, SIMC kicked off the Seoul ADR Festival (organised by KCAB) with a special webinar entitled “The New K-Wave: Evolution in Mediation Practice and Processes”. It featured two panel discussions, with a stellar line-up of distinguished practitioners and corporate users:

Catching the Next Wave in Mediation Practice

- Chungjin Chung (Senior Legal Counsel, Korea Gas Corporation)

- Francis Xavier SC (Regional Head, Dispute Resolution Group, Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP)

- George Lim SC (Chairman, SIMC)

- Moderated by: Kap-You (Kevin) Kim (Senior Partner, Peter & Kim)

Mix and Match: Uncovering the Keys to Success

- Myung-Ahn Kim (Partner / Senior Foreign Attorney, Yoon & Yang LLC)

- Gregory Vijayendran SC (President, Law Society of Singapore / Partner, Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP)

- Michele Park Sonen (Head (North East Asia), Singapore International Arbitration Centre)

- Moderated by: Chuan Wee Meng (CEO, SIMC)

If you’re wondering what is the intersection between the Korean Wave, Squid Game, and international mediation, read on…

Opening Remarks by Ms Sue Hyun Lim

SIMC was honoured to have Ms Sue Hyun Lim (Secretary-General, KCAB International) provide opening remarks at the webinar. Ms Lim noted that on the same day of the webinar, the Korean government had announced the easing of Covid-19 measures and a shift in its policy in dealing with the virus – that it would now focus on living with Covid-19 rather than eradicating it.

Noting the air of cautious optimism in Korea following this announcement, Ms Lim opined that there was a similar sense of hope and optimism regarding international mediation. She stated that in keeping with this trend, there had been a special task force set up to look into making KCAB an institution that promotes international mediation. In fact, the Seoul ADR Festival was initially named the ‘Seoul Arbitration Festival’ in its first edition, but had since been renamed to reflect the changing landscape. In her view, dispute resolution was much more than securing a victory or defeating one’s opponent; it was about finding a mutually beneficial solution to the dispute at hand. This should therefore encourage further uptake of international mediation, and providing users with the necessary information was key to its promulgation.

“Dispute resolution is much more than securing a victory or defeating one’s opponent, but in finding a mutually beneficial solution to the dispute at hand.”

Ms Sue Hyun Lim

Catching the Next Wave in Mediation Practice

The first panel discussion saw its esteemed roll of speakers discuss the changing trends in the practice of mediation, both in Korea and across Asia.

Mr Kim noted that he had recently seen his son (living in London) playing games from his childhood, which were brought into international consciousness by the wildly popular Netflix series, Squid Game.

In the same vein as the Korean Wave – a phrase which has recently gained entry into the Oxford English Dictionary – Mr Kim hoped that there would be a similar, new wave in mediation. In this regard, he observed that more of his clients were bringing up the possibility of mediation in the course of arbitration, which was a good development.

Mr Lim shared that there was healthy growth in the use of mediation internationally, pointing to the growth in SIMC’s caseload from 5 cases in its first year in 2014, to 1-2 large international disputes per week. His observation was that mediation was little-known in Korea about 5 years ago. But today, senior practitioners were now interested in getting trained in mediation. He also shared that he was recently involved in a large mediation in Korea, where parties were involved in 3 arbitrations worldwide but managed to reach an in-principle agreement after 3 days of mediation. The trend was changing from a zero-sum game to achieving what was best for the client – whether mediation, arbitration or a combination.

“My message to Korean lawyers is to come on board now.”

Mr George Lim SC

Mr Xavier traced the history of dispute resolution – from the early days when we traditionally did not have a choice and had to fight it out in the courts, to the present day when arbitration was seen as a more flexible and civil process (but was still a ‘war’). With the rise of mediation, there was a viable alternative to a paper war. He noted that any kind of war was probably not the best way to resolve disputes if you had a non-antagonistic option and you could preserve business relationships. In Mr Xavier’s view, corporations (both large and small) now think about what is the best way to resolve disputes – “It’s not so simple anymore, the world has changed.”

From a user’s perspective, Mr Chung shared that 3 years ago, his organisation did not employ mediation clauses in their contracts at all. He opined that mediation was much cheaper and faster, where parties could have a co-mediator (e.g. a Korean mediator) as a bridge when there were cross-border disputes and cross-jurisdictional parties. There was more reason to mediate where there had been repeated transactions with the same party. In his view, the Korean mentality was not to consider mediation once parties had commenced litigation or arbitration. However, Kogas was one of the biggest importers in the world and wanted to preserve their relationships with their business partners, especially given that it was a small community. “We have to educate people more (such as in-house counsel), on how to use AMA clauses, and how to import mediation clauses.“

Mr Chung also noted that enforceability was one of the common issues raised by sceptics of mediation, given that South Korea had not ratified the Singapore Convention. In response, Mr Lim noted that more time was required for countries to take up the Singapore Convention since national agendas had largely been focused on battling the Covid-19 pandemic. However, in his experience, enforceability was usually not at issue if the settlement agreements were structured well. Further, parties might have had recourse to AMA clauses and processes (such as the SIAC-SIMC AMA protocol) where settlement agreements reached in mediation were recordable as consent arbitral awards and enforceable under the New York Convention.

In the sphere of investor-state disputes, there had been a rise in mediations as well. Mr Xavier shared that mediation was rare in this context almost a decade ago, as treaty arbitration might commonly arise where a new political regime disavowed previous contracts entered into by the exiting government, due to allegations of impropriety. Those governments would prefer to have a third party adjudicate the dispute, rather than negotiate with the investors. Governments were now realising that this would be costly – finances were limited and should not be expended on seemingly endless disputes.

One issue that might crop up in the mediation of such disputes was the coordination required between ministries or national agencies, although this was being mitigated as infrastructure improved. In fact, there had been a sea change and Mr Xavier cited a recent survey where 64% of those polled felt that mediation should be compulsory before ICSID arbitration commenced.

In response to Mr Kim’s question on tips to persuade governments or big companies to settle disputes through mediation, Mr Lim said that the trick was to catch the disputes early so that there was a chance to salvage the relationship. Secondly, mediation is not just about resolving the dispute but in creating value, so that parties are motivated to settle. Unfortunately, many lawyers were not attuned to doing so.

The panellists also discussed the potential issues in disputes with government-linked companies, where there might be a concern that their decision to settle the disputes would later be subject to government audit, and consequently, lead to questions of impropriety being raised. The decision-makers might also have to take direction from the government, which might require justification and even restrain them in some situations. Mr Kim stated in response that it might be helpful to bifurcate the dispute, where some issues could be decided first (for example, by way of a preliminary decision/views by the arbitrators). In his experience, having such an indication from the tribunal might facilitate the parties’ settlement, insofar as they had a sense of the decision that might be rendered.

“We are myopic, lawyers trained in the art of war… But there is a bigger thing, there is the future to build together.”

Mr Francis Xavier SC

Mr Xavier opined that there was a temptation not to take responsibility for disputes. But if boards, presidents, and CEOs of companies changed their mindsets to focus on how to make the situation a win-win, and put on their creative hats, they could come up with the solution. If that did not work, they might then have to resort to the second option (i.e., arbitration/litigation).

Mr Lim also shared on a recent mediation which involved a China state-owned company, and the fact that they came to SIMC showed that it was a trusted institution. This was where mediation institutions could add value. He also shared on the importance of structuring the mediations for big disputes, where parties might have to return to their management and consider the options on the table. He cited the example of an SIMC investor-state mediation he had recently conducted, where parties were left with 3 options and had indicated their preference. Online mediations might also allow the key decision makers to join and leave the process for a few hours at critical junctures. Further, mediation institutions could collaborate to set the lead for inter-cultural disputes to be resolved (for example, via co-mediation with mediators from different cultures and backgrounds).

Mix and Match: Uncovering the Keys to Success

Warning: Squid Game references ahead!

The second panel discussion delved into the processes in international mediation which have gained a foothold in recent times.

Ms Sonen shared that arbitration and mediation did not have to be competing, they could be complementary and you could use them to achieve very creative and flexible ways to resolve the dispute quickly and effectively, in a way which was genuinely satisfying for the parties.

“Lawyers are not just expected to fight the war, but to assess the situation accurately and provide an objective view about where the client may be situated within the arbitration or litigation. If the lawyer fails or refuses … that is not helpful to the client.“

Ms Myung-Anh Kim

Mr Vijayendran opined that: “The operational assumption is that you go into mediation in good faith … this means a real commitment or sincerity to find a solution … this doesn’t have to be a Squid Game where it’s me versus you.” However, legal practitioners were dealing with an educational curve which meant being able to share pointers about mediation to their clients, as well as clear up myths and psychological barriers (e.g., mediation might be seen as a sign of weakness when parties were gearing up for ‘battle’).

How does a mixed mode dispute resolution, such as AMA, add value to the process?

Ms Sonen explained the mechanics of the AMA process, and the enforceability brought about by the New York Convention, as well as the time and cost savings. Even if the dispute did not settle at that point, mediation could really narrow down the issues in disputes which could help the arbitration move faster and more efficiently. In some cases, it might make sense for the mediation to be a little later, if you had a very technical dispute where you wanted to sort out the facts first, or you needed document production for fact-intensive disputes. But you could mediate way before the hearing where a significant amount of costs would be incurred. Mediation also gives parties more flexibility and the ability to preserve relationships.

Mr Chuan noted that there was a strong wall of confidentiality between SIAC and SIMC, which assured parties that what was discussed during mediation would not be divulged to SIAC or the arbitrator – this allowed parties to be very open and creative in mediation.

According to Ms Kim: “In the bigger scheme of things, facilitating a settlement via a structured mechanism with a confidentiality wall in place and executed well will be in the best interests of everyone. Certainly, it is one of the practical commercial approaches which we had advised our clients on.”

For those wondering about the interplay between mediation and arbitration, Mr Vijayendran opined that “the basic proposition is that the mediator’s win is not the arbitrator’s loss. … It is essentially something that could turbo boost the dispute resolution at the appropriate juncture.”

How is online mediation compared to in-person mediations or hearings? Is it harder to connect?

Ms Kim says it was a “yes” and “no”. There was a challenge in talking to a screen and having to guide parties through the process, especially where it was their first time. However, it helped to take away the emotive and unnecessary part of the discussions, so that parties can focus on the key substantive issues on the table.

Costs, comfort levels, conduciveness, connections and collaborative approach – are the 5 Cs that Mr Vijayendran had observed. Online mediations reduced costs from travelling, and professional costs. It was also a convenient and efficient means of achieving access to justice.

“This type of accessibility means the sky is the limit, you can Zoom in from any part of the globe, from your living room.”

Mr Gregory Vijayendran SC

However, more was needed from the mediator to make people feel at ease, as he would not have as much of a feel of the people in the room. Conduciveness came from confidentiality, which parties had to be assured of before being candid and creative. As for connections – the technology had to work. Lastly, a collaborative approach has to be in place, to work with the professional and help the parties see that they were part of the solution.

Flexibility was one of the cornerstones for ADR’s appeal in cross border disputes – disputes could be resolved online and this would be as effective as resolving them in-person. While there might be some downsides, such as less camaraderie, it was worth the time and costs savings in many cases. Most importantly, the start of an arbitration did not mean that the negotiation phase had ended – we could be flexible and creative to use the arbitration process to facilitate settlement, such as by flushing out the issues and coming to a genuine settlement.

How is mediation more effective as a process compared to mutual negotiation between lawyers?

The experience which Mr Vijayendran had in co-mediating a case with Mr Yoshihiro Takatori (Yoshi-san) under the JIMC-SIMC protocol illustrated the value proposition that mediators can bring to the table. That case involved a cross border dispute between Japanese and Indian parties. “We had a beautiful experience of two heads being better than one. … you become a natural sort of cultural bridge … and the other facet you bring to bear is the understanding of different legal systems.”

He also noted that it might be awkward being the practitioner who was in the arena – simultaneously trying to put his best foot forward while at the same time being pacifist – it was much easier for an independent and objective third party to work with parties to find solutions.

Mr Vijayendran* and his co-mediator, Yoshi-san were also quick to nip in the bud any suggestion that they were not appointed by each party to represent their respective interests. “To use another Squid Game reference, I was not there to take his marbles away or him to take mine, we always spoke in one voice.” As co-mediators, they were unified and concerted – and there were winners all round in this game.

How is diversity important in mediations, for example, having a female and male co-mediator?

The panellists felt that success in mediation boiled down to having the right calibre and substantial expertise of the mediator at hand. However, empathy was also a strong quality in mediation, and one needed to have high EQ. Further, given that different people from different backgrounds might look at an issue differently, having diversity on the mediation panel might be useful in coming up with a creative and commercial solution.

Conclusion

SIMC would like to extend its thanks to KCAB International for its generous support in this webinar, as well as to all speakers for their wonderful contributions. We hope that the above panel discussions answers your questions on the recent trends in international mediation, which will continue to grow and evolve rapidly in the coming years.

*For more information, please refer to Mr Vijayendran and Yoshi-san’s co-mediation experience here.